In a number of corporate environments, the usual exfiltration channels (e.g. email, web uploads, …) are both actively monitored and restricted. Whilst some companies only allow remote access via a company-issued laptop and VPN, some allow remote connections in (usually via the likes of Citrix). This gives rise to an interesting use-case whereby we control the host but not the guest.

Problem statement

The aim is to find an out-of-band channel through which we can exfiltrate files with 100% accuracy, using only the tools available on the guest. This means installing things like Python is usually out of the question as they either get flagged or flatly blocked - and tools like Powershell would look very out of place on say, a financial controller’s PC.

There is however a very powerful toolset pretty much guaranteed to be installed on a user’s PC - a browser with a JS console. Will that be sufficient? Challenge accepted…

Ze masterplan

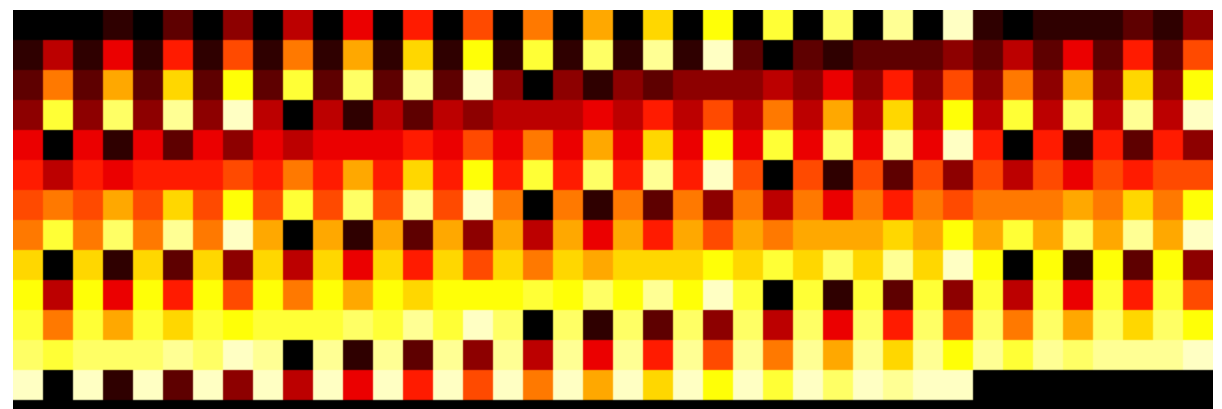

A file is nothing more than a collection of bytes. By converting each byte to a colour (or in our case, each half-byte), it’s a bit like colouring a chessboard where square A1 represents the first byte, A2 the 2nd etc… - and maybe 0x0f is represented as red, 0xee as blue etc…

The host is tasked with identifying where that chessboard is being displayed, parsing each square back into its respective byte, and re-assembling the file.

Here is what a file composed of 0x00 to 0xff looks like, with each half-byte represented by a square (so 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 0x1 for 0x00 0x01 respectively):

The guest

The key component behind this is the canvas element in HTML5. Drawing a coloured square is as simple as:

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.rect(startX, startY, sqWidth, sqWidth);

ctx.fillStyle = '#000000';

ctx.fill();

ctx.closePath();

The second (and perhaps more imporant) one is the ability to read a file as an array of bytes, provided by the FileReader API.

const fr = new FileReader();

fr.onload = () => {

const data = fr.result;

let array = new Uint8Array(data);

We then essentially iterate through the file and display each byte accordingly. For larger files we need to paginate and add metadata at the bottom representing the SHA1 hash of the data displayed on a page. This will be used by the host to validate the integrity of the data decoded.

Note that pagination is set up to happen automatically once the ‘play’ button is pressed - essentially the pages will start to flip at the user-defined interval.

The host

The host part consists of 2 sections - one to take screenshots, and one to extract the data.

Screenshot automation

I wasn’t keen on relying on 3rd party tooling so I wrote a quick bit of PowerShell to help out. The trick was to string together a couple of API calls to (1) find the active window, (2) get its coordinates and dimensions before finally (3) taking a capture and saving it to disk. This meant importing a number of functions from user32.dll such as GetWindowRect.

The process is then repeated for as many times as required - which should be at least the number of pages displayed by the guest (and more). The host will automatically deal with duplicate snaps.

Data extraction

Given a screenshot, we first need to find what is called a ‘region of interest’ in computer vision. This calibration region is going to be a large black rectangle on the first capture - this will help us derive the coordinates of the canvas in subsequent captures.

This is currently done (shamelessly) using Python’s cv2 module:

img = cv2.imread(args.image, cv2.IMREAD_UNCHANGED)

ret, threshed_img = cv2.threshold(

cv2.cvtColor(img, cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY), 127, 255, cv2.THRESH_BINARY

)

contours, hier = cv2.findContours(threshed_img, cv2.RETR_TREE, cv2.CHAIN_APPROX_SIMPLE)

We iterate through the contours to find the one that matches the (etimated) canvas size on the guest. Note this won’t be an exact match - e.g. if the guest is displaying 1200x800, we may get 1202x802.

Armed with the position of the canvas, we can extract the chessboard-like patterns of subsequent snaps and parse those accordingly. The metadata at the bottom of each page is used to tell us which page we are currently procesing. We also perfrom a SHA1 hash of the parsed data and compare that with the SHA1 available in the metadata. If the two match then the page has been parsed correctly and the output is written to ‘

Re-assembly

Data extracted from each screenshot follows a <page num>_<sha1 of page> pattern. Re-assembling them is as simple as doing a cat * > out.bin. For final verification we can take the SHA256 of the file and compare it to the one displayed on the guest.

The caveats

Resolution

The need for accurracy is essential. This might not seem too important for text files but for binaries it could essentially render the file unusable. This meant that instead of displaying each byte as a pixel, we instead chose to display each half-byte as an NxN square. There is also some weighting in place to ensure that the center of a square is weighted more heavily that its edges, which helps recover the ‘true’ colour.

Colour scale

Technically we could display 3 bytes in each pixel as each of the RGB components takes 0-255 as a value. However remote desktop protocols use all sorts of clever trick to reduce bandwidth utilisation - and sometimes that means messing around with the colours.

To work around any compression in place we use the full RGB spectrum to represent 0x0 to 0xf - this means that the whole 255^3 range is roughly divided into 16 buckets. This isn’t very efficient but does allow us to recover data perfectly.

Using cv2

‘Parsing’ a screenshot might seem a little like overkill - there could well be a way to achieve the same results using say, a full screen mode. If you do, feel free to add this to pixfiltrator and send me a merge request!

Speed

Using a default canvas size of 1200x800 and representing each half-byte as a 5x5 square, each page contains (1200x800)/25/2 bytes - or around 19KB without taking the metadata into account. Given the larger resolutions available nowadays this can easibly be increased, but does give a good lower bound. A 190KB file would take 10 pages - and at a rate of one page per second, that’s 10s. I’ll let you do the maths but if you have gigs to transfer out this probably isn’t it.

Conclusion

So did it work? Well - yes! This has been tested over Citrix with low bandwidth (non-local WiFi) and files were recovered with 100% accuracy. Mission, accomplished.

Mitgations

This is a hard one - the guest code is simple enough to type by hand. There might be a way to run browsers in some sort of sandbox mode that restricts access to the FileReader API.

Taking it further

I wonder if it’s be possible to use a similar mechanism to instead display each page as a QR code. QR parsing is blazingly fast nowadays, so this could be an alternative too - though it would require more libraries client-side, which is something our original brief tried to avoid.

References

The project is available here. Forks and MR are actively encouraged!